Please click HERE for original article on Neurosciencenews.com

Summary: Mouse models of corticospinal injuries reveal adult neurons begin a natural regeneration process by reverting back to an embryonic state. The regeneration is sustained with the help of a gene more commonly associated with Huntington’s disease. - Source: UCSD

When adult brain cells are injured, they revert to an embryonic state, according to new findings published in the April 15, 2020 issue of Nature by researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, with colleagues elsewhere. The scientists report that in their newly adopted immature state, the cells become capable of re-growing new connections that, under the right conditions, can help to restore lost function.

Repairing damage to the brain and spinal cord may be medical science’s most daunting challenge. Until relatively recently, it seemed an impossible task. The new study lays out a “transcriptional roadmap of regeneration in the adult brain.”

“Using the incredible tools of modern neuroscience, molecular genetics, virology and computational power, we were able for the first time to identify how the entire set of genes in an adult brain cell resets itself in order to regenerate. This gives us fundamental insight into how, at a transcriptional level, regeneration happens,” said senior author Mark Tuszynski, MD, PhD, professor of neuroscience and director of the Translational Neuroscience Institute at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

Using a mouse model, Tuszynski and colleagues discovered that after injury, mature neurons in adult brains revert back to an embryonic state. “Who would have thought,” said Tuszynski. “Only 20 years ago, we were thinking of the adult brain as static, terminally differentiated, fully established and immutable.”

But work by Fred “Rusty” Gage, PhD, president and a professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and an adjunct professor at UC San Diego, and others found that new brain cells are continually produced in the hippocampus and subventricular zone, replenishing these brain regions throughout life.

“Our work further radicalizes this concept,” Tuszynski said. “The brain’s ability to repair or replace itself is not limited to just two areas. Instead, when an adult brain cell of the cortex is injured, it reverts (at a transcriptional level) to an embryonic cortical neuron. And in this reverted, far less mature state, it can now regrow axons if it is provided an environment to grow into. In my view, this is the most notable feature of the study and is downright shocking.”

To provide an “encouraging environment for regrowth,” Tuszynski and colleagues investigated how damaged neurons respond after a spinal cord injury. In recent years, researchers have significantly advanced the possibility of using grafted neural stem cells to spur spinal cord injury repairs and restore lost function, essentially by inducing neurons to extend axons through and across an injury site, reconnecting severed nerves.

When adult brain cells are injured, they revert to an embryonic state, according to new findings published in the April 15, 2020 issue of Nature by researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, with colleagues elsewhere. The scientists report that in their newly adopted immature state, the cells become capable of re-growing new connections that, under the right conditions, can help to restore lost function.

Repairing damage to the brain and spinal cord may be medical science’s most daunting challenge. Until relatively recently, it seemed an impossible task. The new study lays out a “transcriptional roadmap of regeneration in the adult brain.”

“Using the incredible tools of modern neuroscience, molecular genetics, virology and computational power, we were able for the first time to identify how the entire set of genes in an adult brain cell resets itself in order to regenerate. This gives us fundamental insight into how, at a transcriptional level, regeneration happens,” said senior author Mark Tuszynski, MD, PhD, professor of neuroscience and director of the Translational Neuroscience Institute at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

Using a mouse model, Tuszynski and colleagues discovered that after injury, mature neurons in adult brains revert back to an embryonic state. “Who would have thought,” said Tuszynski. “Only 20 years ago, we were thinking of the adult brain as static, terminally differentiated, fully established and immutable.”

But work by Fred “Rusty” Gage, PhD, president and a professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and an adjunct professor at UC San Diego, and others found that new brain cells are continually produced in the hippocampus and subventricular zone, replenishing these brain regions throughout life.

“Our work further radicalizes this concept,” Tuszynski said. “The brain’s ability to repair or replace itself is not limited to just two areas. Instead, when an adult brain cell of the cortex is injured, it reverts (at a transcriptional level) to an embryonic cortical neuron. And in this reverted, far less mature state, it can now regrow axons if it is provided an environment to grow into. In my view, this is the most notable feature of the study and is downright shocking.”

To provide an “encouraging environment for regrowth,” Tuszynski and colleagues investigated how damaged neurons respond after a spinal cord injury. In recent years, researchers have significantly advanced the possibility of using grafted neural stem cells to spur spinal cord injury repairs and restore lost function, essentially by inducing neurons to extend axons through and across an injury site, reconnecting severed nerves.

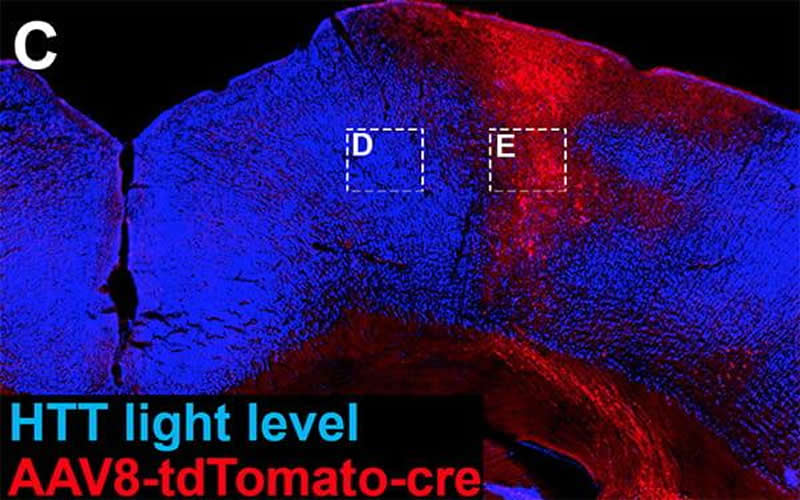

A cross-section of a rat brain depicts cells (in blue) expressing normal levels of the Huntingtin gene while cells (in red) have had the gene knocked out. The latter cells, without the Huntingtin gene, displayed less regeneration. The image is credited to UC San Diego Health Sciences.

Last year, for example, a multi-disciplinary team led by Kobi Koffler, PhD, assistant professor of neuroscience, Tuszynski, and Shaochen Chen, PhD, professor of nanoengineering and a faculty member in the Institute of Engineering in Medicine at UC San Diego, described using 3D printed implants to promote nerve cell growth in spinal cord injuries in rats, restoring connections and lost functions.

The latest study produced a second surprise: In promoting neuronal growth and repair, one of the essential genetic pathways involves the gene Huntingtin (HTT), which, when mutated, causes Huntington’s disease, a devastating disorder characterized by the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain.

Tuszynski’s team found that the “regenerative transcriptome” — the collection of messenger RNA molecules used by corticospinal neurons — is sustained by the HTT gene. In mice genetically engineered to lack the HTT gene, spinal cord injuries showed significantly less neuronal sprouting and regeneration.

“While a lot of work has been done on trying to understand why Huntingtin mutations cause disease, far less is understood about the normal role of Huntingtin,” Tuszynski said. “Our work shows that Huntingtin is essential for promoting repair of brain neurons. Thus, mutations in this gene would be predicted to result in a loss of the adult neuron to repair itself. This, in turn, might result in the slow neuronal degeneration that results in Huntington’s disease.”

Co-authors include: Gunnar Poplawski, Erna Van Nierkerk, Neil Mehta, Philip Canete, Richard Lie, Jessica Meves and Binhai Zheng, all at UC San Diego; Riki Kawaguchi and Giovanni Coppola, UCLA; Paul Lu, UC San Diego and Veterans Administration Medical Center, San Diego; and Ioannis Dragatsis, University of Tennesee.

The latest study produced a second surprise: In promoting neuronal growth and repair, one of the essential genetic pathways involves the gene Huntingtin (HTT), which, when mutated, causes Huntington’s disease, a devastating disorder characterized by the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain.

Tuszynski’s team found that the “regenerative transcriptome” — the collection of messenger RNA molecules used by corticospinal neurons — is sustained by the HTT gene. In mice genetically engineered to lack the HTT gene, spinal cord injuries showed significantly less neuronal sprouting and regeneration.

“While a lot of work has been done on trying to understand why Huntingtin mutations cause disease, far less is understood about the normal role of Huntingtin,” Tuszynski said. “Our work shows that Huntingtin is essential for promoting repair of brain neurons. Thus, mutations in this gene would be predicted to result in a loss of the adult neuron to repair itself. This, in turn, might result in the slow neuronal degeneration that results in Huntington’s disease.”

Co-authors include: Gunnar Poplawski, Erna Van Nierkerk, Neil Mehta, Philip Canete, Richard Lie, Jessica Meves and Binhai Zheng, all at UC San Diego; Riki Kawaguchi and Giovanni Coppola, UCLA; Paul Lu, UC San Diego and Veterans Administration Medical Center, San Diego; and Ioannis Dragatsis, University of Tennesee.

ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

Source:

UCSD

Media Contacts:

Scott LaFee – UCSD

Image Source:

The image is credited to UC San Diego Health Sciences.

Original Research: Closed access

“Injured adult neurons regress to an embryonic transcriptional growth state”. by Gunnar H. D. Poplawski, Riki Kawaguchi, Erna Van Niekerk, Paul Lu, Neil Mehta, Philip Canete, Richard Lie, Ioannis Dragatsis, Jessica M. Meves, Binhai Zheng, Giovanni Coppola & Mark H. Tuszynski.

Nature doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2200-5.

Abstract

Injured adult neurons regress to an embryonic transcriptional growth state

Grafts of spinal-cord-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) enable the robust regeneration of corticospinal axons and restore forelimb function after spinal cord injury1; however, the molecular mechanisms that underlie this regeneration are unknown. Here we perform translational profiling specifically of corticospinal tract (CST) motor neurons in mice, to identify their ‘regenerative transcriptome’ after spinal cord injury and NPC grafting. Notably, both injury alone and injury combined with NPC grafts elicit virtually identical early transcriptomic responses in host CST neurons. However, in mice with injury alone this regenerative transcriptome is downregulated after two weeks, whereas in NPC-grafted mice this transcriptome is sustained. The regenerative transcriptome represents a reversion to an embryonic transcriptional state of the CST neuron. The huntingtin gene (Htt) is a central hub in the regeneration transcriptome; deletion of Htt significantly attenuates regeneration, which shows that Htt has a key role in neural plasticity after injury.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed